Chinese Pioneers in Santa Cruz County: 1850-Today

Agriculture 农业

Chinese laborers first came to the Monterey Bay Peninsula to work as laborers in the fields. Land owners, looking for cheaper labor, brought in Chinese workers from San Francisco to help with the harvest. When local indigenous labor became scarce, Chinese immigrants raised their daily rate to two dollars a day in response to the demand. Despite this, Chinese workers were willing to work longer hours, under harsh conditions, and for less money.

Read More: Agriculture 农业

Abalone Rush 鲍鱼产业

Fishermen coming from China in the early 1850s must have been pleasantly surprised to find Monterey’s coastal waters brimming with abalone. While dried abalone is a delicacy in China, it was abundant in California. The Chinese gold miners who were having no luck finding gold in the mountains, moved to the shore to try their luck harvesting abalone. Dozens of Chinese came to Monterey each week setting up shacks along the shores of Point Lobos, Point Joe, and Point Sur. At first, only abalone meat had value, and the shells were stacked along the walls and on the roofs of the worker’s cabins. But soon there was a market for abalone shell jewelry and furniture and the shells were exported by the thousands.

Read More: Ocean Gold

Fishing 鱼业

Since there was no way to export fresh fish from Monterey to other markets, the fish that was caught had to be preserved, and that meant drying it. Drying fish required skill and knowledge, both of which the Chinese workers had. They knew which fish had to be hung to dry and which could be spread out; which fish could be dried whole and which ones had to be cleaned, and which ones needed to be on racks and which ones could be put in the open air. This knowledge eventually gave them a monopoly in the market.

Read More: Ocean Gold

Railroads 铁路

Like many of the small beach towns along the northern California coast, Santa Cruz was often cut off by winter storms and isolated by mountain terrain. The road between Santa Cruz and Watsonville was so dangerous that it was cheaper to cut lumber, haul it down the mountain, and sail it by ship around to ports in San Francisco than it was to travel by road. At least that was true until the railroads showed a new way to travel.

In 1873, businessmen Claus Spreckles and Frederick Hihn invested in a railroad that would finally cross the mountain between San Jose, Santa Cruz, Soquel, and Aptos – connecting crops in Santa Cruz County with ports in Alameda and San Francisco. With money from a subsidy approved by county voters, the track was laid by a mostly Chinese workforce.

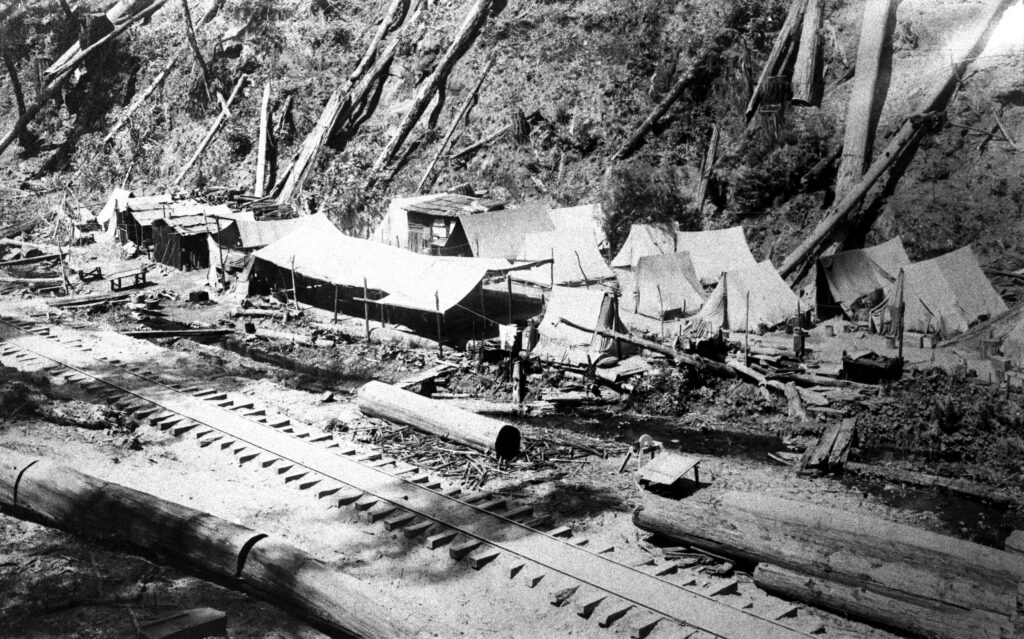

Between 1875 and 1880, the Chinese built three different railroads in Santa Cruz County. They drilled 2.6 miles of tunnel and laid 42 miles of track. But it was dangerous work. Accidents were common and Chinese laborers were often given the most dangerous jobs. It is said that for each mile of track, one Chinese laborer died.

The Chinese who worked on the railroad lived in tents about a mile away from the work-site. They worked six days a week, ten hours a day, and were paid a dollar a day. Two dollars a week was deducted from their pay for food.

Read More: The Railways That Shaped Santa Cruz And the Chinese Pioneers Who Built Them

The Chinese come to Santa Cruz 圣克鲁兹的中国人–1850

The presence of Chinese workers in Santa Cruz began in the mid-1850s with the economic boom in the area. Many of the Chinese found work further south in Monterey and Salinas in fishing and agriculture. But a new trend was literally booming just a little up north. The first Chinese in Santa Cruz began working in manufacturing, mainly limestone and lumber. When explosive powder dried up due to the Civil War, Santa Cruz found a new market. In 1861, California Powder Works opened in San Lorenzo, a mile up-river from Santa Cruz. In 1864, they readily hired 12 Chinese laborers, representing the largest group of Chinese working together in the Santa Cruz area to date.

However, with numbers comes visibility and with visibility comes fear. Local newspapers at the time worried that the Chinese workers were taking jobs away from “honest, hard working white men.” They even declared that if these workers were killed in the dangerous factories “it will not be much loss to the community.” The feeling of isolation and dislike floated on the surface of all relationships the Chinese people had in the community.

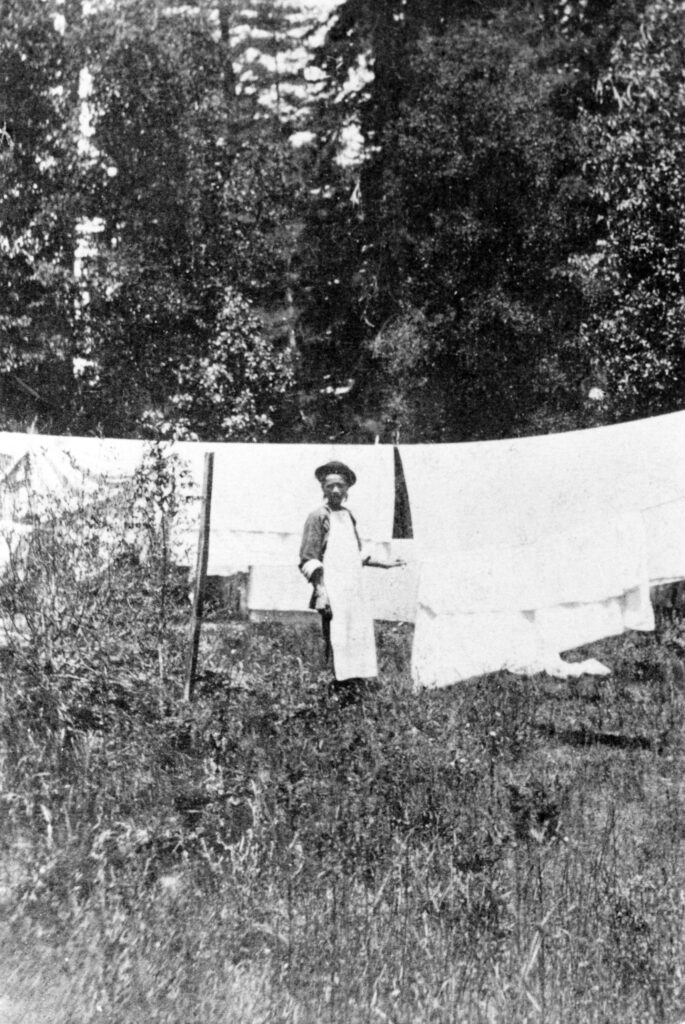

In every way, the Chinese laborers were kept separate from other workers at the Powder Works. They handled their own food and laundry. They were not even paid individually. All their meager pay went to a foreman who then paid the others.

By the 1870s, California Powder Works employed 35 Chinese laborers. They averaged 19 years old and worked predominantly as coopers, manufacturing the heads, hoops, and stays of the barrels in which the blasting powder was stored. It was said to be the most dangerous job and yet while the 70 white men who worked in other parts of the plant were paid from $2.50-$3.00 a day, the Chinese coopers were paid $1.00 a day. The Chinese workers were seen as a necessity if the company were to remain competitive, yet they were not seen as equal. California Powder Works continued to hire Chinese laborers until July 1878 when, bowing to local anti-Chinese pressure, they fired all their Chinese workers.

The First Chinatown 第一个唐人街

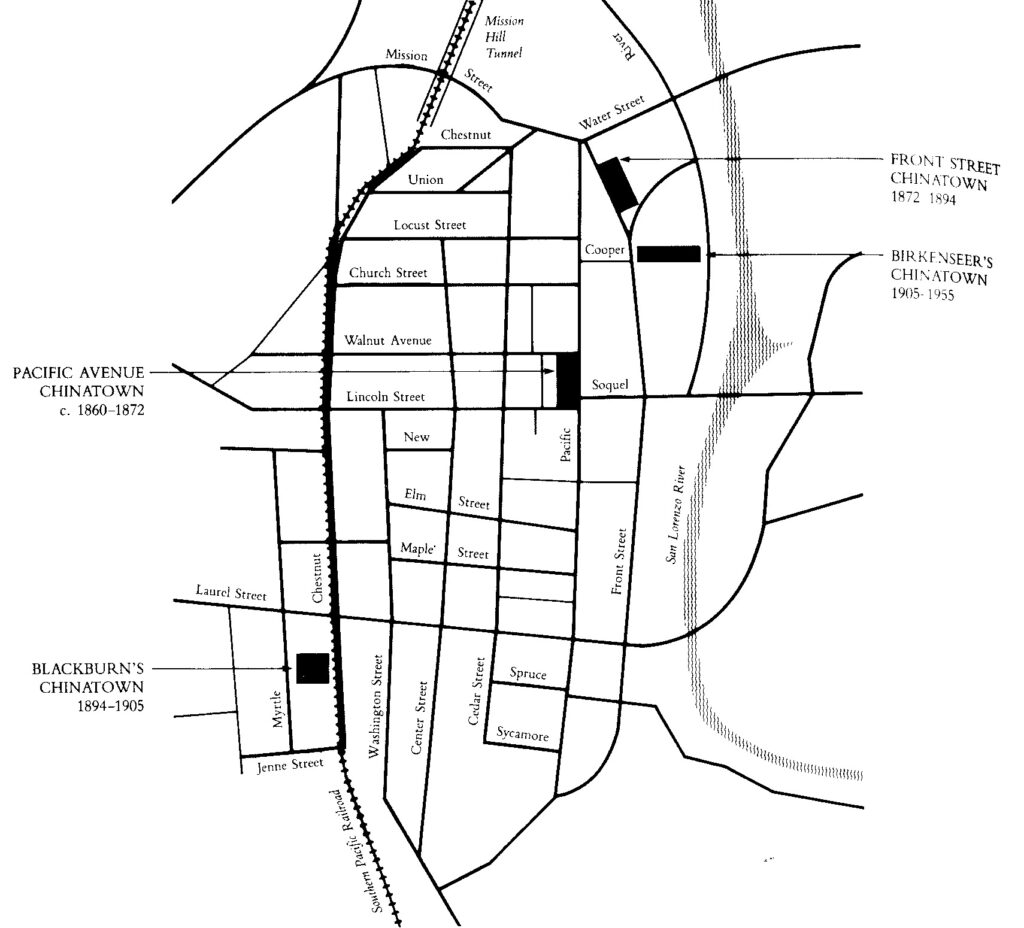

The first Chinatown in Santa Cruz came together in the mid 1860s and was located on the west side of Willow Street (what is now Pacific Ave.) A collection of 12 men took up most of one block between Lincoln and Walnut Streets. In a group of single-story buildings, there were two laundries, a temple, one or two small stores, and a cigar shop that catered to whites in the community.

As Santa Cruz’s economy began to boom in the late 1860s, South Willow Street began to become inundated with businesses relocating to areas where the rents were more affordable. This pushed the Chinese from Willow Street, to vacant buildings along Front Street. By 1877 the last Chinese moved from Willow Street location to the new Front Street Chinatown, which consisted of 37 men and one woman. There were 31 laundrymen, two cooks, one domestic, and one merchant. Of the 98 Chinese people living in Santa Cruz at that time, less than half lived in Chinatown. Most lived at their place of work: the railroad depot, the laundry, or as a domestic.

Read More: Five Chinatowns | 5 个中国城

Chinese Laundries 中国人运营的洗衣房

Laundry is not as exciting as railroads, or as dangerous as making explosives. But the laundry business, good and bad, provided newly-immigrated Chinese workers with a way to build a business and grow roots in the community. Opening a wash house did not require a lot of capital investment, just a lot of hard work. Because of the hard work involved, there was less competition.

Chinese in Santa Cruz soon had a monopoly on wash houses and swiftly organized to take advantage of their leverage, decreasing competition between laundries and fixing rates at a stable price. This remained true until the invention of the modern steam laundries and the restriction of Chinese immigration eventually put them out of business.

By 1910, only 10 Chinese laundrymen remained in Santa Cruz. But at their peak, Chinese-owned wash houses dominated Santa Cruz and the towns and cities of the Bay Area.

The Displacement of Chinatown

The Front Street Chinatown was the hub of local Chinese culture in Santa Cruz until April 14, 1894. That night, a fire broke out on the east side of Front Street and quickly spread through Chinatown. The exact cause of the fire was never found, but before it was done, it had burned Chinatown to the ground. Within a week, however, the Chinese were rebuilding. They were offered two new locations where they could move; one was on a small island of land in the San Lorenzo River, the other was a piece of the Blackburn property. Two separate leaders in the Chinese community stepped forward and each signed a lease agreement for Chinatown to move to their new location.

The fire did not make Chinatown disappear, but it succeeded in tearing the community in half. Now there were two Chinatowns, the San Lorenzo River Chinatown and the Blackburn Chinatown.

In September, 1905, Southern Pacific Railroad announced it was going to buy the land the Blackburn Chinatown was renting and building a new depot in the location. Once again, Chinatown was being displaced. With no secure foothold in the community, Chinatown members began to leave the area. Some moved to the San Lorenzo River Chinatown, some chose to leave entirely. Observances, feasts, and festivals declined as the entire Chinese community dwindled. By the 1920s fewer than 50 Chinese remained in Santa Cruz.

The few families that remained in Santa Cruz’s Chinatown remember it as a quiet, multicultural community. The Lee and the Ow families remember a Chinatown filled with Black, Filipino, and Italian residents. Chinese children were expected to speak English at school and Chinese at home, constantly caught between two worlds. Life in Chinatown remained this way until flooding of the San Lorenzo River finally condemned the last buildings. The remains of Santa Cruz’s last Chinatown were raised following the major flood of 1955.

The Chinese Markets and Restaurant 中国超市和饭店

The dwindling population of Chinese in Santa Cruz would continue with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This immigration restriction act refused entry into the United States to any Chinese “employed in mining, fishing, huckstering, peddling, laundrymen, or those engaged in taking, drying or otherwise preserving shell or other fish for home consumption” – every part of the economy in which Chinese people had participated and excelled. About the only thing Chinese were allowed to enter the United States to do was be a merchant. This worked out well for businesses opening within Chinatown and other Chinese communities. They had a built-in support group and little competition and a built-in support. But when large chain stores started to arrive in Santa Cruz in the 1940’s, Chinese merchants were pushed to the sides of the market.

Chinese merchants in the 1940s had to reinvent the idea of a small market and appeal to customers whose needs were not being met by the larger companies. Chinese markets became known for being open long hours and all days of the week. They often catered to a multicultural population, and carried merchandise not found anywhere else, allowing Chinese markets to survive alongside the larger markets.

By Flex Kids Culture.