Legacy on the Shore: The Untold Story of Chinese Pioneers in Bay Area

Beneath the quiet fields, along the windswept coast, and behind the faded names of towns like Monterey, Watsonville, and Santa Cruz, lies a history few remember—but none should forget.

In the 1800s, waves of Chinese immigrants came to California’s central coast. They fished the seas, farmed the land, carved railroads through mountains. They built communities, raised flags on Independence Day, and fought for dignity in a land that didn’t want them. Much of what they created is gone. Many of their names were never recorded. But their legacy still lives in the soil, the stories, and the families who remain.

This is the story of the Chinese in the Bay Area. Not as outsiders. As founders.

They Came Without Gold, But Brought Treasure

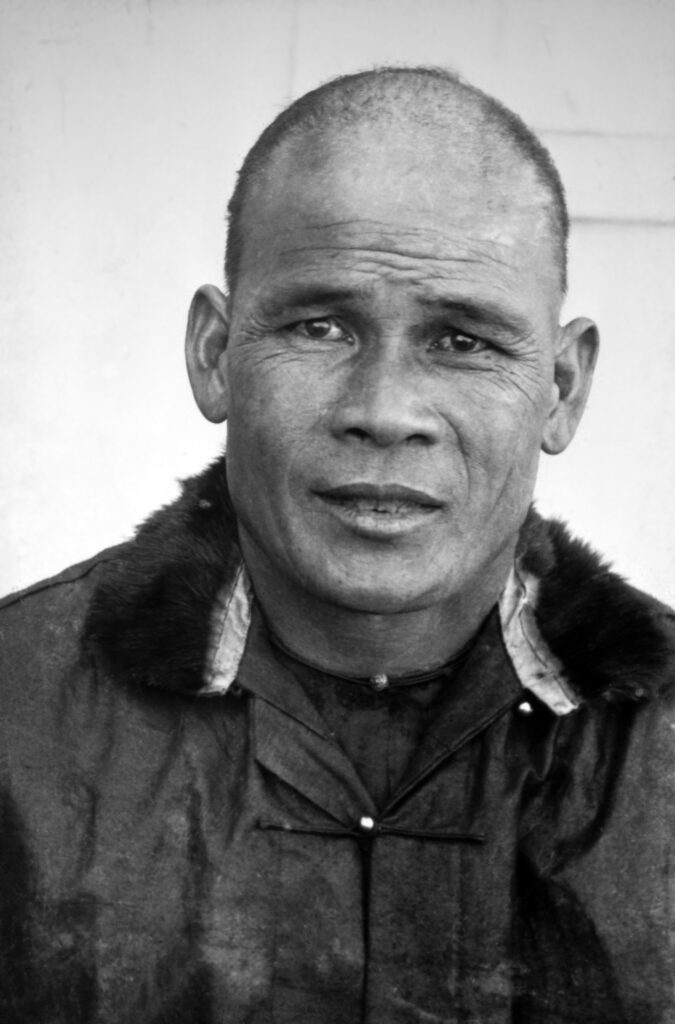

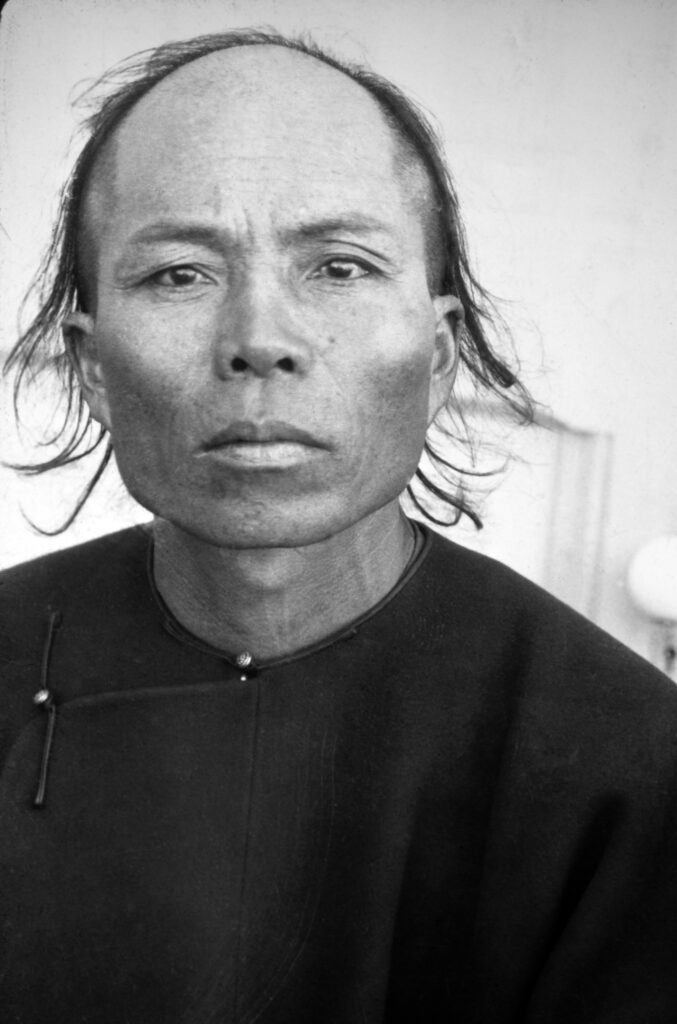

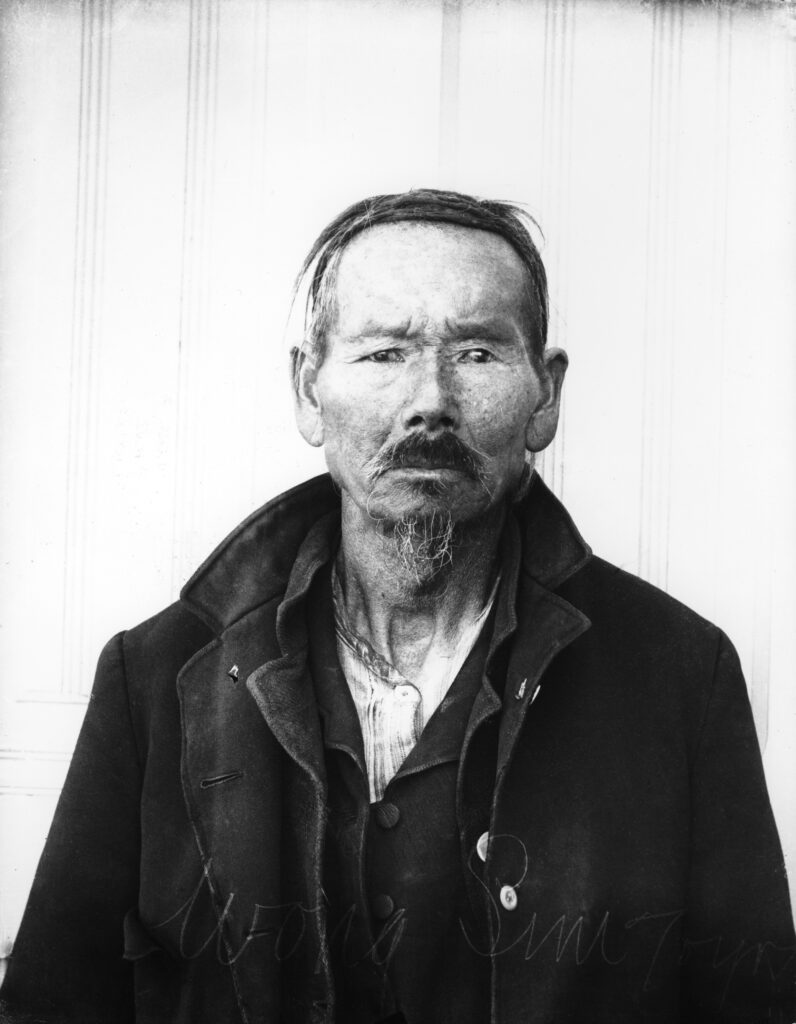

In the mid-1800s, Chinese immigrants began arriving on California’s coast. Most were from Guangdong province, traveling across the Pacific in search of opportunity—what they called the “Gold Mountain.” But many didn’t come for literal gold. They came to fish, farm, build, survive. Some arrived in Monterey Bay, stepping onto shores that would become home—and hardship—for generations.

They wore cotton clothes, their hair in long braids. They didn’t come with wagons or guns, like the stereotypical pioneers of the American West. Instead, they came by sea, with calloused hands and quiet strength.

They Built the Foundations—And Were Erased From Them

The Chinese in the Monterey Bay area were not guests in history. They were builders.

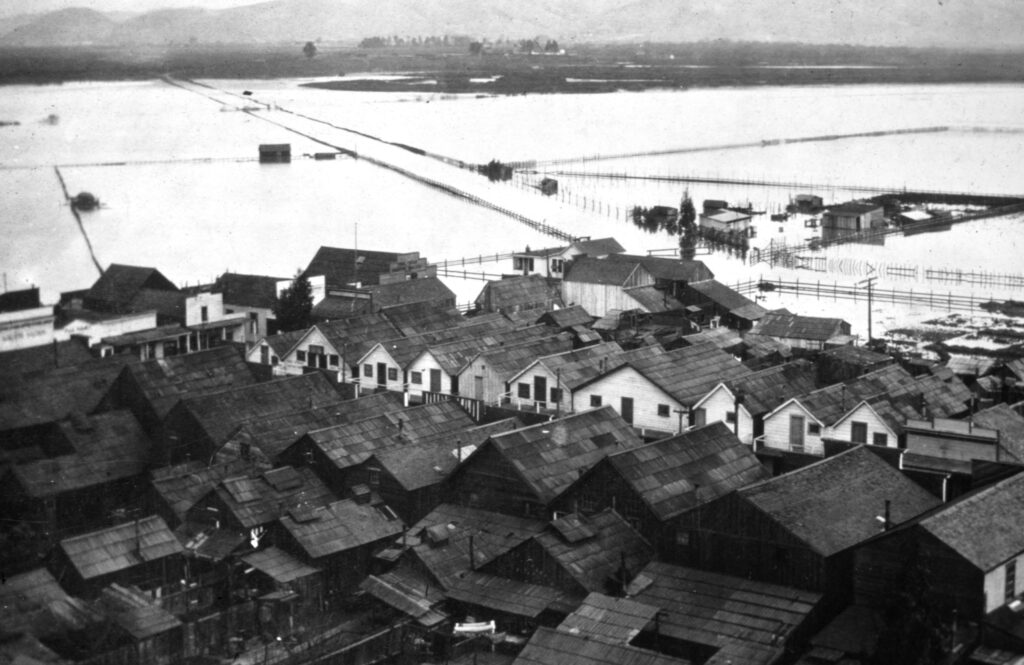

In Monterey, they created the fishing industry: drying abalone and catching squid long before it became local cuisine. In Watsonville and Salinas, they drained swamplands and turned them into thriving farmland. In Santa Cruz, they carved through mountains and laid tracks for the railroad. A haunting story from 1879 tells how dozens of Chinese workers died in a tunnel explosion during railroad construction—some burned alive while trying to rescue others.

“They laid the railroad that built America,” people said. But history barely said their names.“

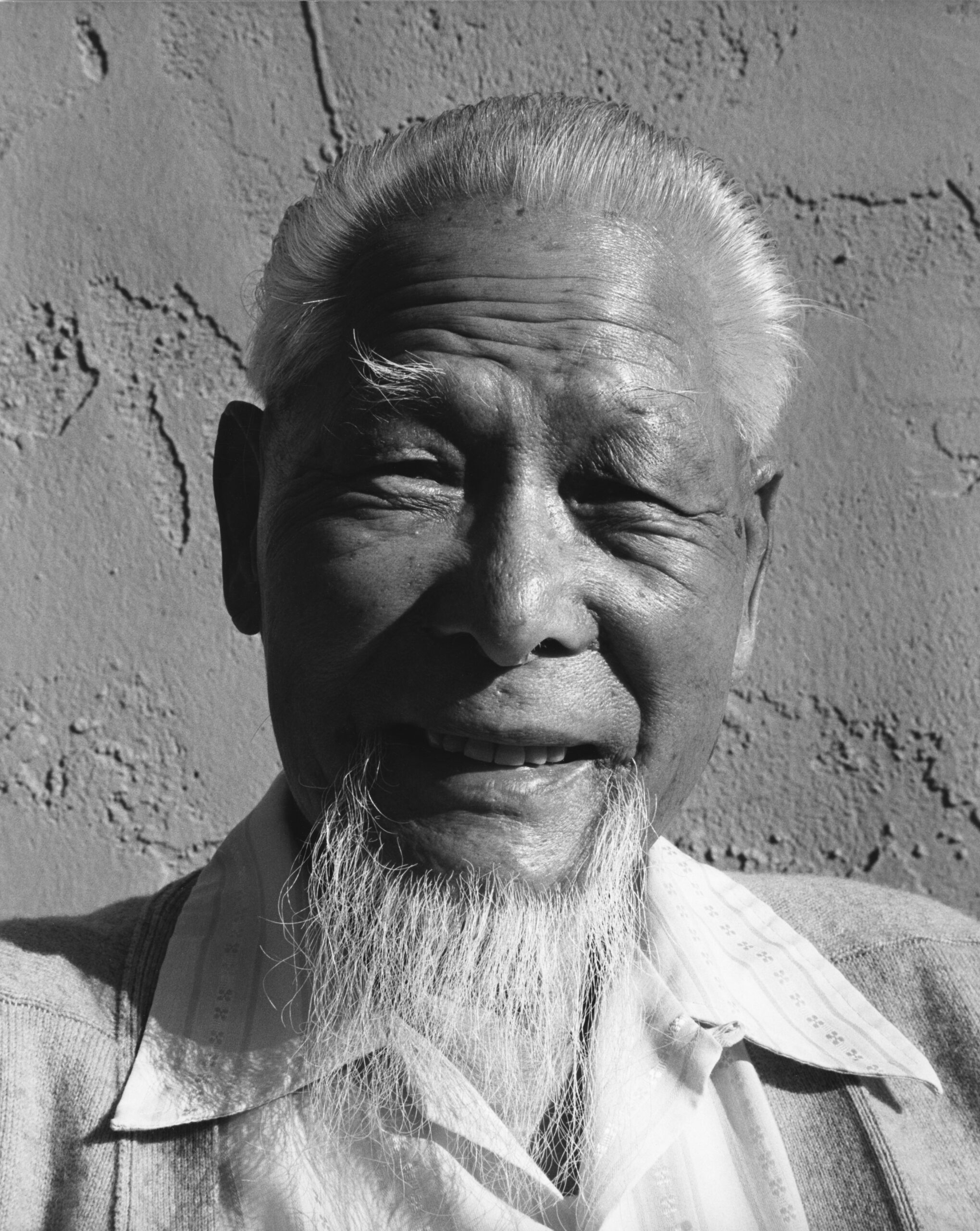

Forgotten in the Books, Remembered in the Bones

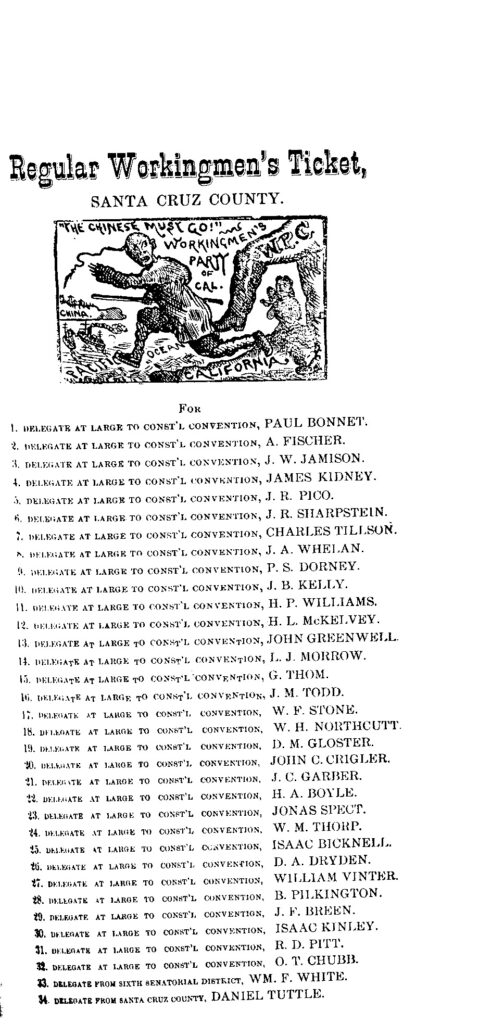

In the histories written by white settlers, Chinese names rarely appeared. A newspaper once listed every ethnic group that shaped Pajaro Valley—except the Chinese. Their work was essential, but their presence was treated like a footnote. Even after decades of contribution, they remained outsiders.

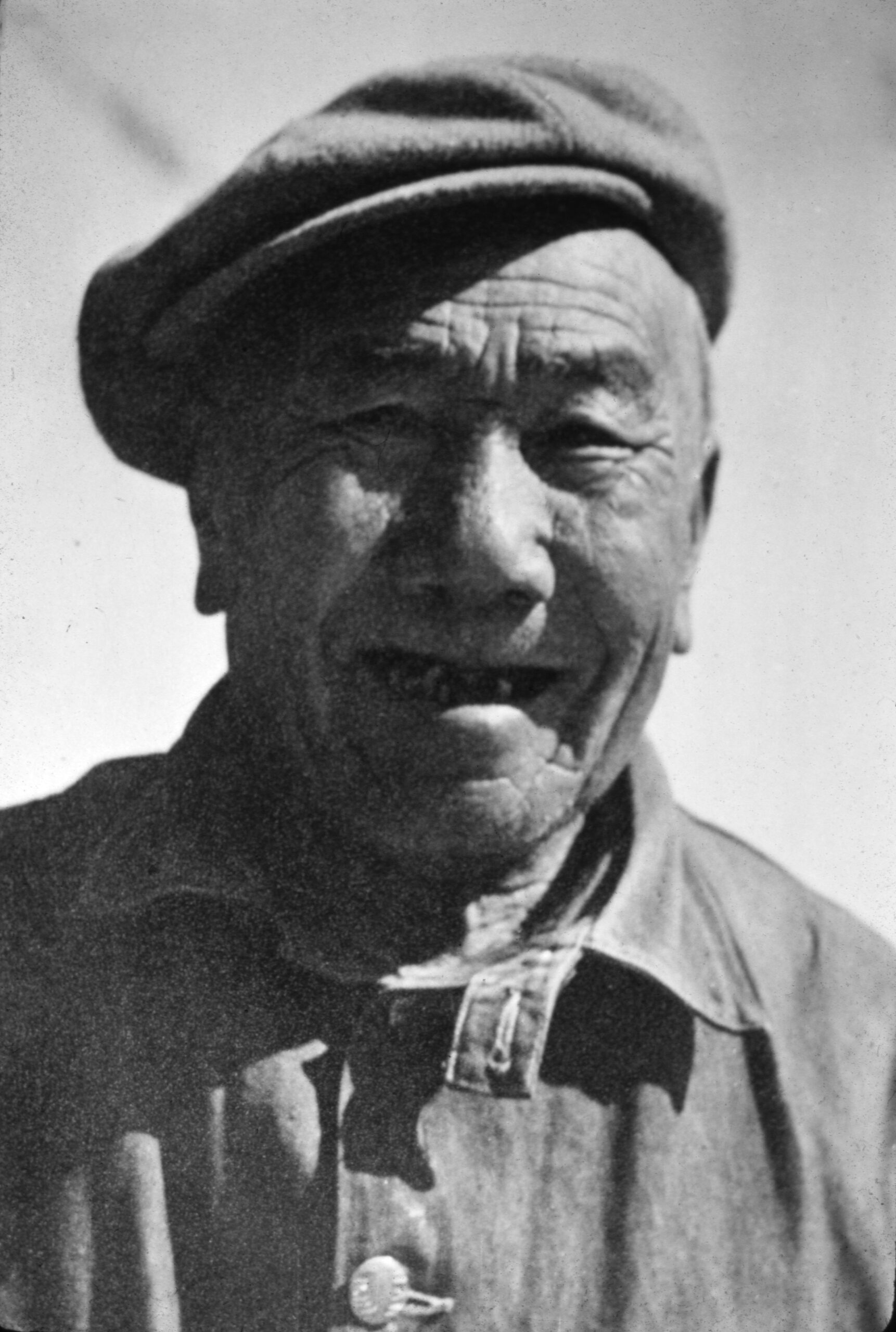

When they died, many did not expect to stay. They had no family with them, no property, and little place in society. So they were buried temporarily. Years later, bones were dug up, scrubbed clean with wine and water, packed into wooden boxes, and shipped back to China—to be returned to the home they never got to see again.

“In 1913 alone, over 10,000 boxes of bones were sent home from American soil.”

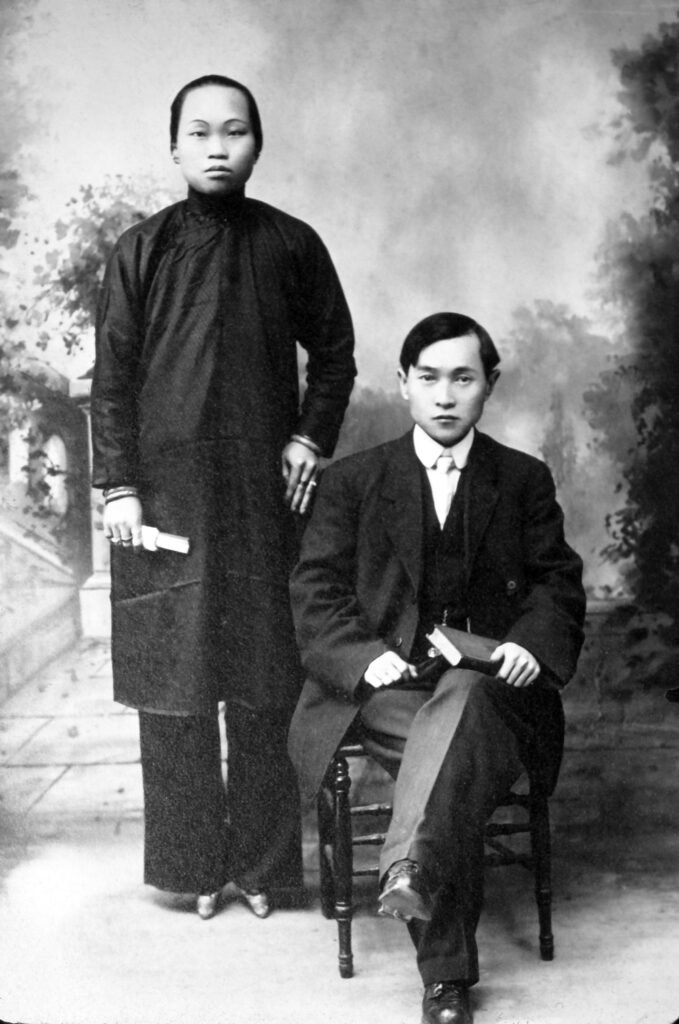

Threatened Homes, Unyielding People

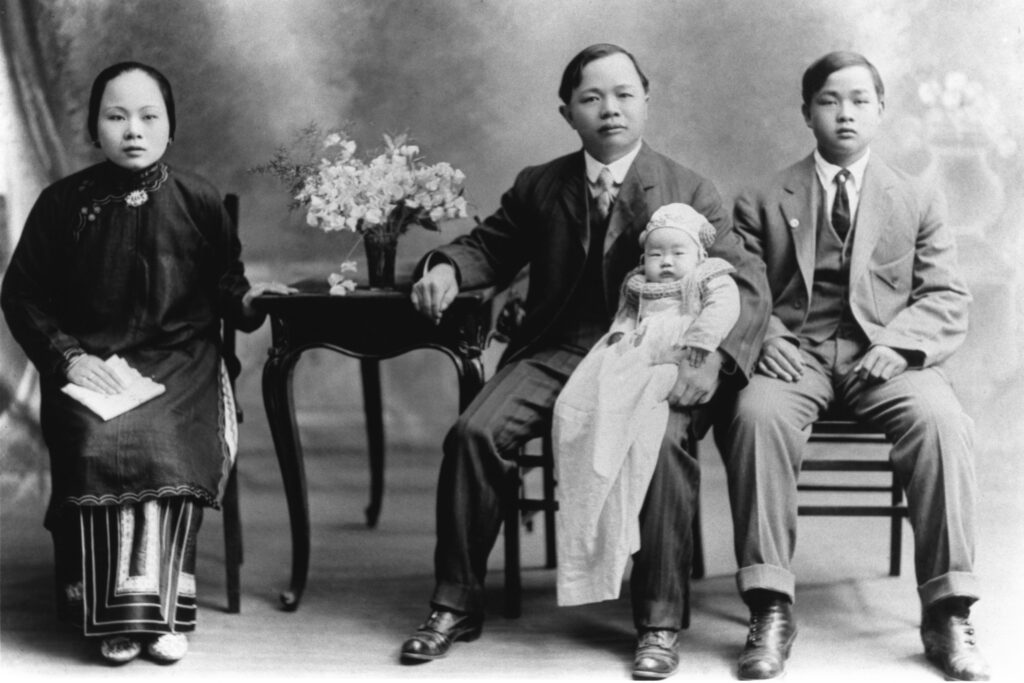

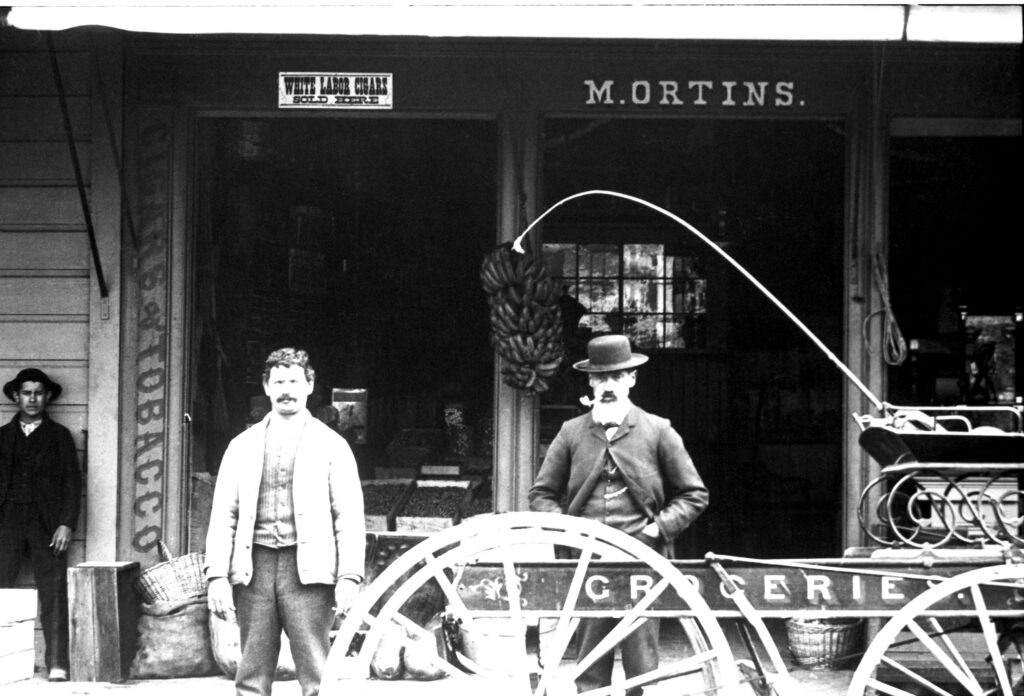

In every major town across the Monterey Bay—Monterey, Watsonville, Santa Cruz, Salinas—there once stood Chinatowns. More than neighborhoods, they were sanctuaries: places where Chinese immigrants could find safety, community, and a sense of identity in a world that often saw them as outsiders.

But those spaces were never fully secure. Some Chinatowns were burned to the ground. Others, like Watsonville’s, were forced to relocate entirely—moved across the county line in a calculated act of survival, negotiated by Chinese community leaders to avoid growing hostility. In places like Monterey, the destruction was permanent; its Chinatown was reduced to ashes and never rebuilt.

beside him, and six of their children.

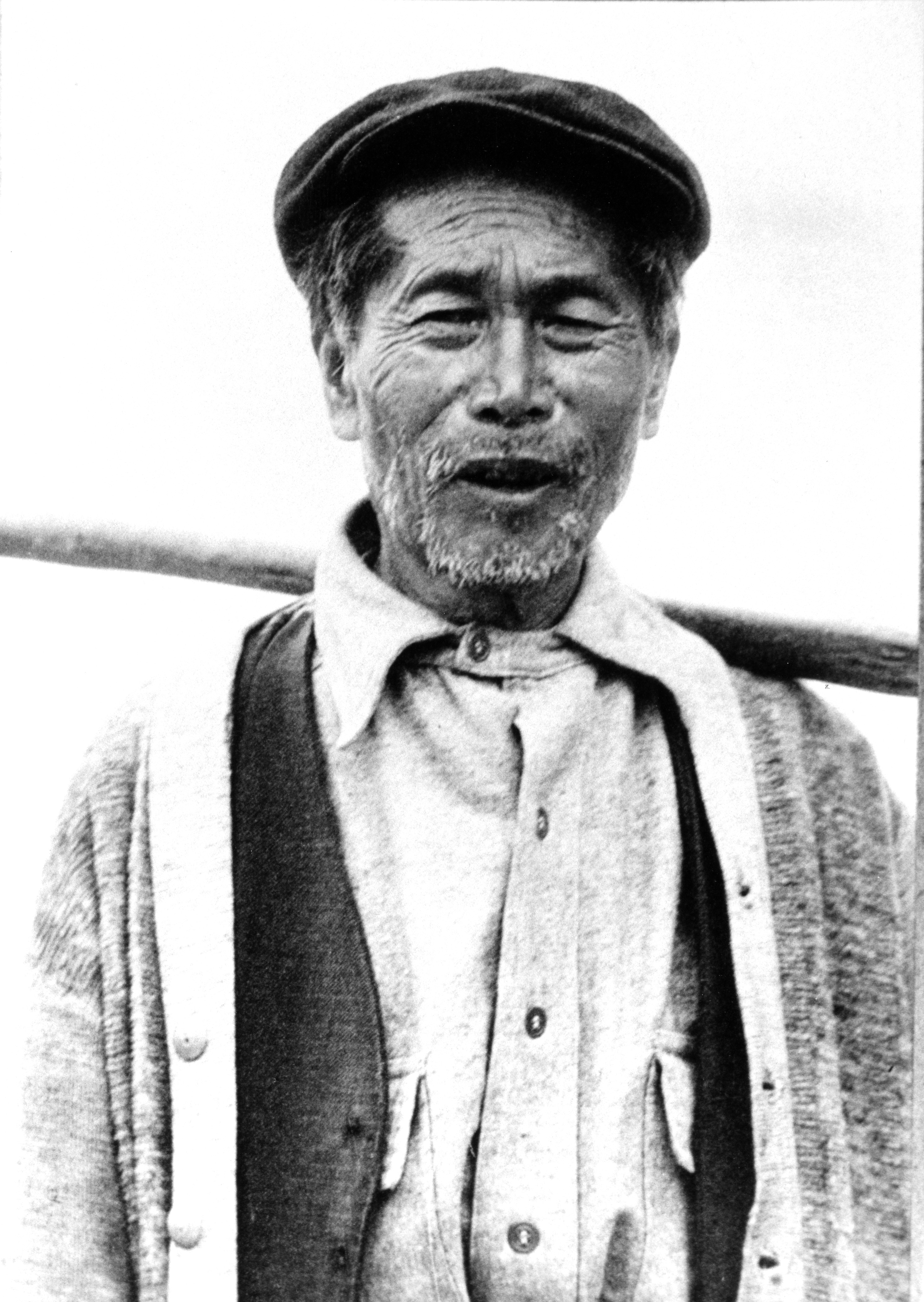

Still, Chinese residents did not remain silent.

When injustice struck, they responded with strength and resolve. After a tragic tunnel explosion killed dozens of Chinese railroad workers, the survivors refused to return to the site until conditions improved. Fishermen took legal action against Portuguese whalers who destroyed their nets. In Santa Cruz, when a Chinese resident was killed, community members demanded answers and respect.

These were not just stories of endurance—they were acts of courage. Quiet resistance. Bold negotiation. Strategic survival. Even with no legal protection and limited rights, the Chinese communities of the Monterey Bay refused to disappear.

Legacy: The Living Echoes

Despite discrimination, surveillance, and laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882–1943), Chinese Americans endured. Their children became shop owners, teachers, local leaders. People like George Ow Sr., who built one of Monterey Bay’s largest businesses, and Emma Dong, a pioneering activist, carried the legacy forward.

And still, many descendants today can’t trace their family histories before the 1900s—because the records were erased, and many ancestors had to use fake names just to enter the country.

This Page Is a Memorial

Every field tilled, every track laid, every fish caught and salted—these weren’t just acts of labor. They were the building blocks of a new life. A life often denied, but never fully erased. So when we speak of Monterey Bay’s past, of its beauty and bounty, we must speak of the Chinese hands that helped shape it. Their stories are not side notes. They are the main thread.